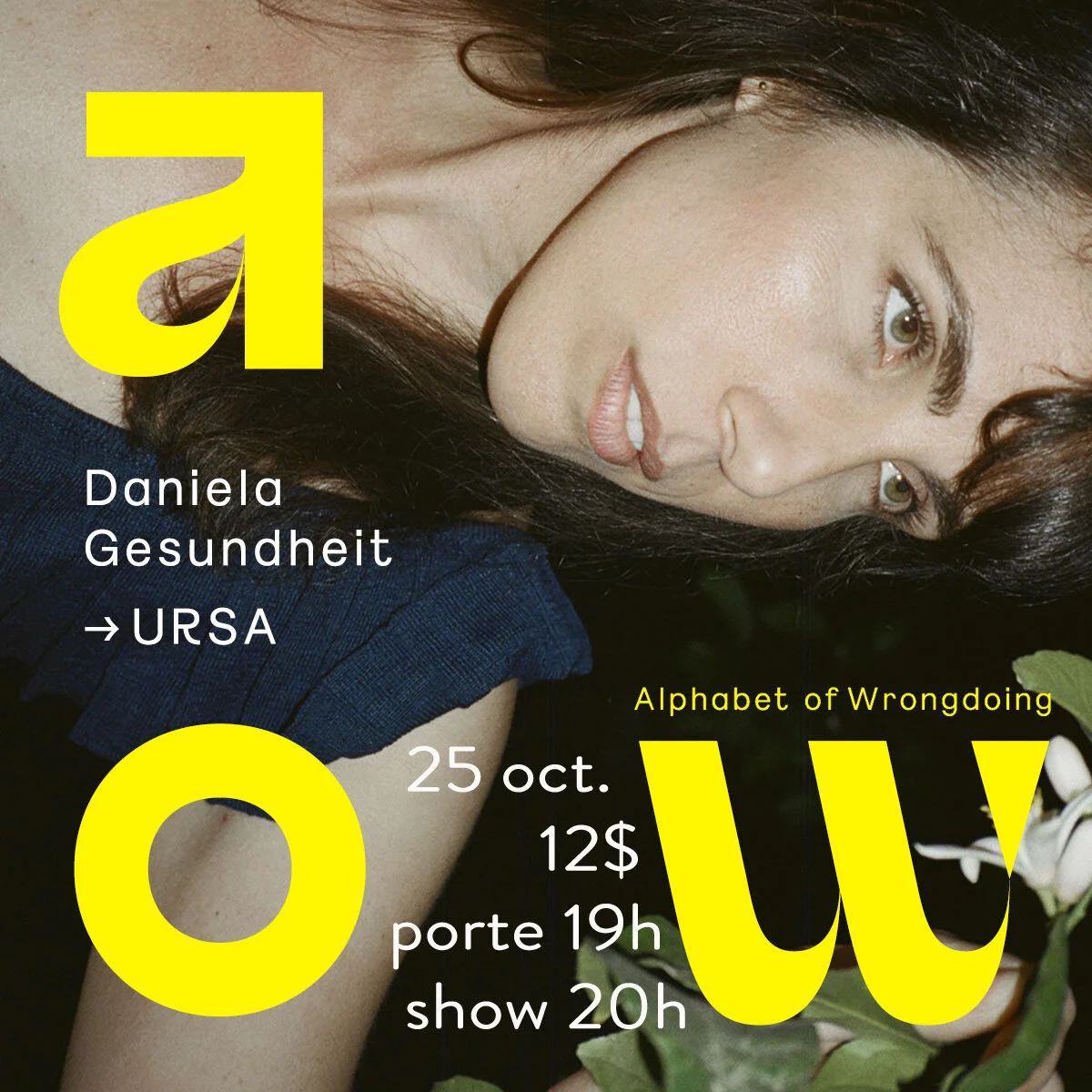

Snowblink’s Daniela Gesundheit reimagines Jewish prayer music for a secular audience

by Tabassum Siddiqui

for The Globe and Mail

When Daniela Gesundheit was a young girl growing up in Los Angeles, while her Jewish parents would attend their Reform synagogue, perched high up in the mountains, she’d often duck outside to partake in her own form of spirituality: communing with nature.

“I always had a hard time with communal religion,” admits Gesundheit, an acclaimed singer-songwriter best known for her indie-folk band Snowblink, noting that while she attended a Jewish day school and learned Hebrew through her youth, her family wasn’t particularly observant, practicing their own pieced-together traditions over the years.

So it’s perhaps surprising that Gesundheit’s new musical project isn’t more of the dreamy melodic soundscapes that made Snowblink mainstays on the Toronto indie scene, but rather an album of traditional Jewish prayer songs usually performed during High Holidays services.

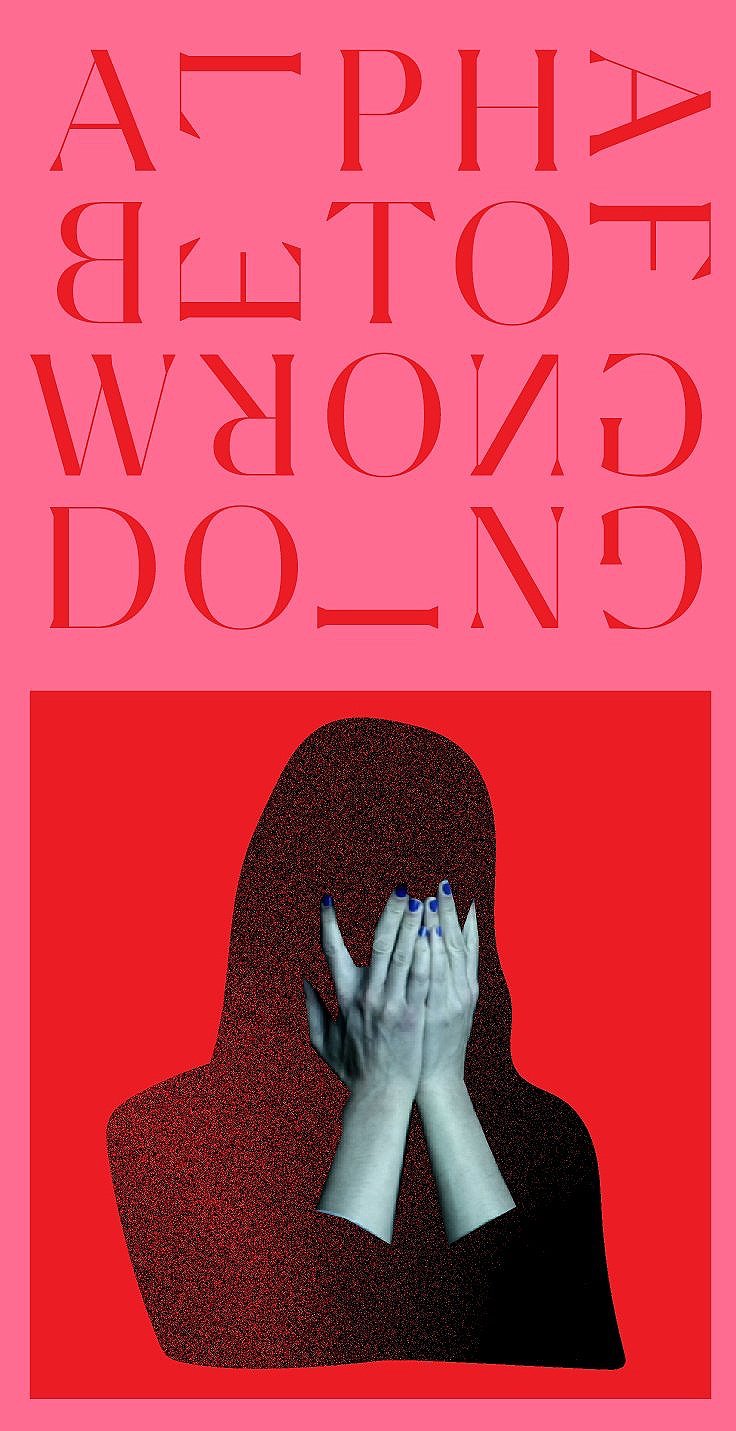

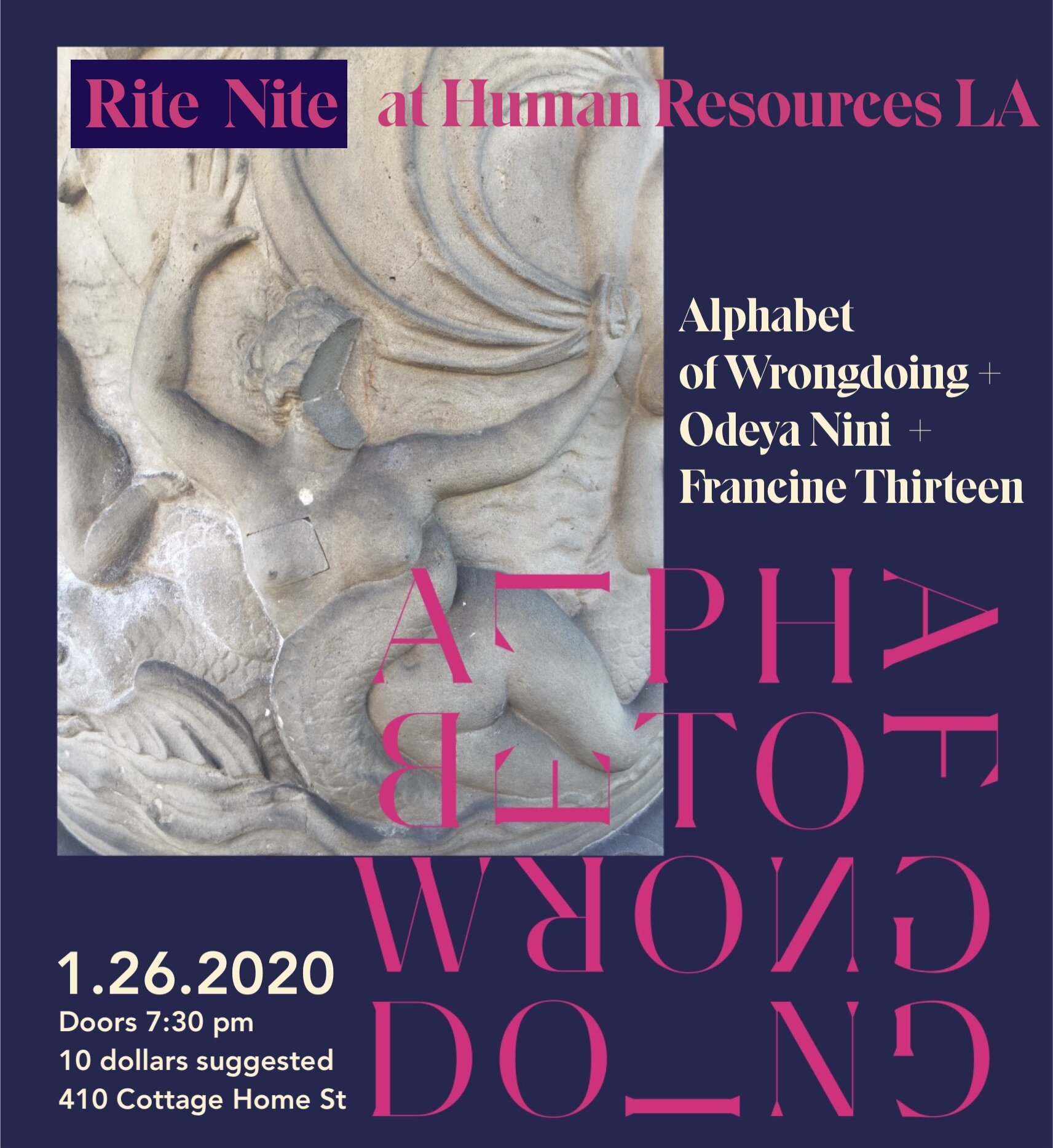

Born partly out of Gesundheit’s work as a cantor (someone who leads the musical liturgical segments of Jewish religious services) at Toronto’s Shir Libeynu congregation for the past 12 years, Alphabet of Wrongdoing maintains the original melodies and text of traditional Jewish prayers and blessings on the themes of reckoning, forgiveness, mortality and atonement, while reimagining them for a secular audience. Another twist: In Orthodox communities, these prayers are traditionally performed by men.

“I would sing this music every year in a ritual context, and be so moved by it, and feel everyone around me be so moved by it – I kind of avoided recording it for a long time, because it felt so important,” Gesundheit says during a recent visit back to Toronto for the High Holidays (she moved back to L.A. a few years ago, but returns often to reunite with her musical peers here).

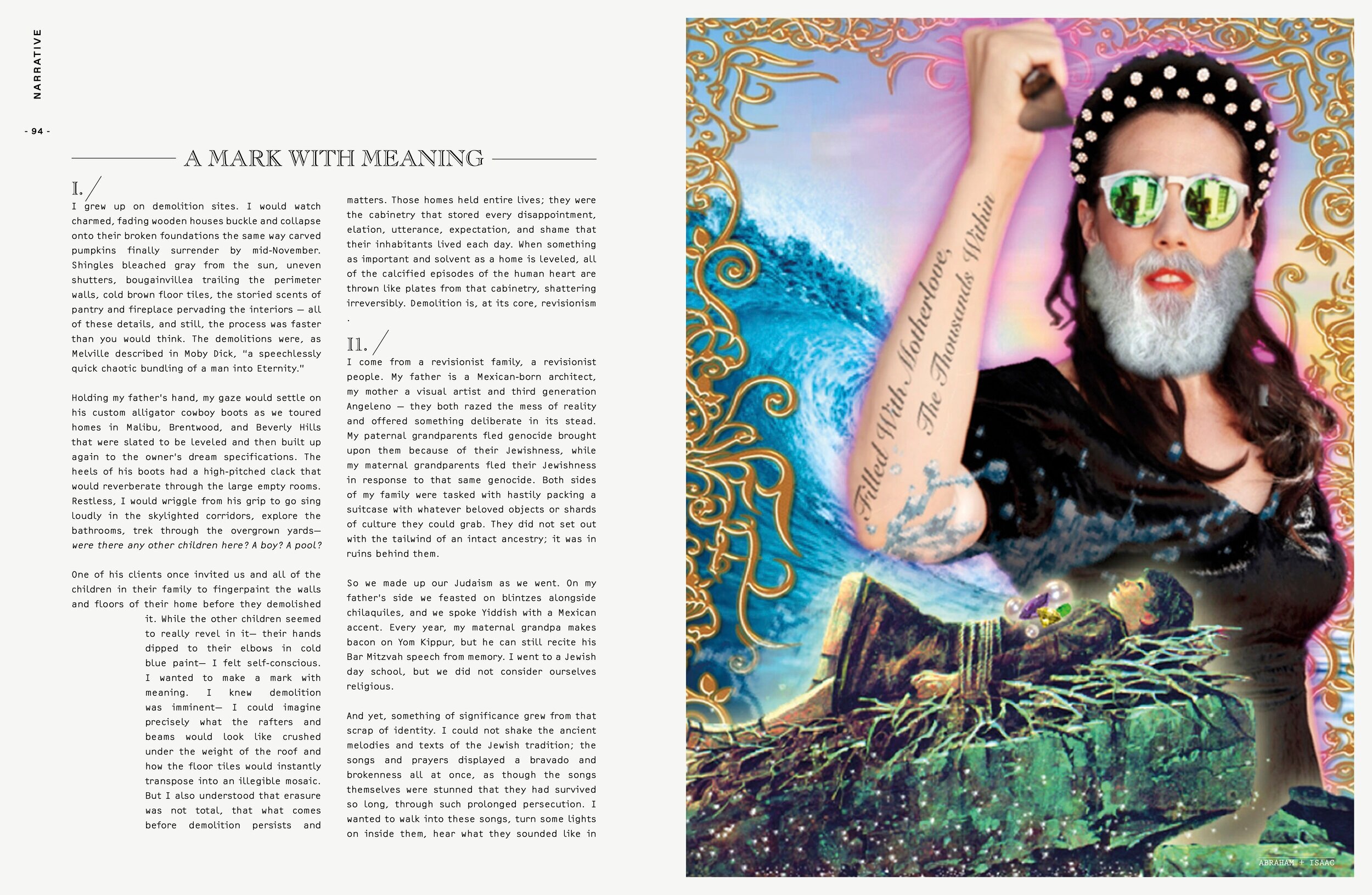

Her path to discovering the beauty in liturgical Jewish music began during her time studying at Wesleyan University in Connecticut. She eschewed joining any of the Jewish groups on campus in favour of creating her own rituals, listening on Yom Kippur to every version of Kol Nidre (All Our Vows), the Aramaic chant typically recited at synagogue on the holiday, she could find at the school library. That appreciation for the deep poetry and strong melody inherent in Jewish prayer songs led her to write her senior thesis on the music of Jewish grieving rituals (renowned writer Maggie Nelson was Gesundheit’s adviser after none of her male professors would take on overseeing the paper).

After becoming a musician and moving to Toronto, Gesundheit found a spiritual home in Shir Libeynu, an inclusive synagogue space open to all that has welcomed female rabbis and cantors over the past 25 years.

“Daniela brings soulful meaning to all the liturgy,” says Shir Libeynu rabbi Aviva Goldberg. “She is able to access the core meaning of the words of the prayers with an honest clarity and accessibility even for those who do not understand the language.”

“I’ve always kept my cantorial work and other music separate for a long time, but a few years ago, it felt like I needed more integration, to bring those lives together,” Gesundheit says. “The record’s been done for a while, and it took me months to even send an e-mail about it to anybody – I was scared, truthfully, to be very publicly Jewish. But I’m proud, and I have a lot to share and say about [the album], so I know it’s the right time to do it.”

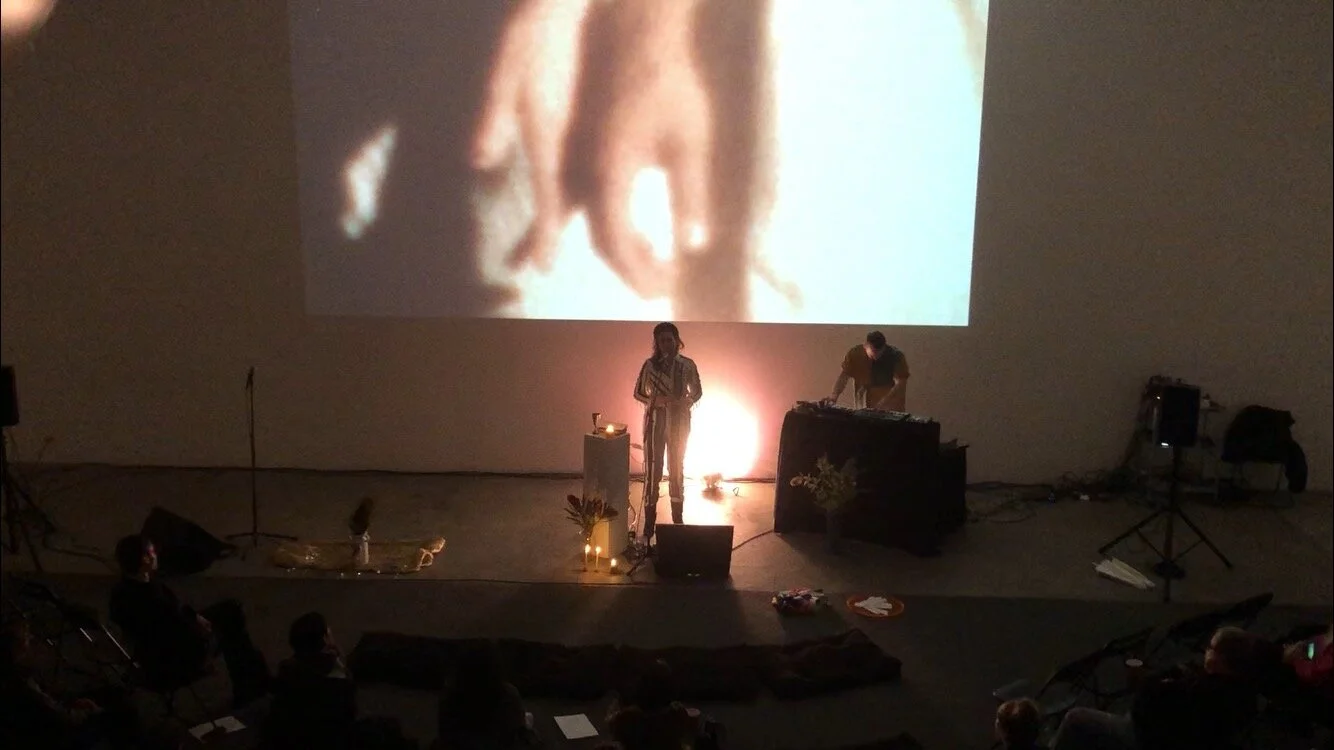

The initial seeds for Alphabet of Wrongdoing were planted a few years ago when fellow Toronto musician Jennifer Castle asked Gesundheit to perform some prayers before a show in L.A. as a way of “purifying” the space. Afterwards, “all these super-cool art kids came up and wanted to talk about it, and the response was one of such curiosity and intrigue that it sparked the idea for me that it was possible to share this music with people and there could be meaning to it,” Gesundheit says.

Alphabet of Wrongdoing features 18 tracks, most of which will be familiar to Jewish listeners used to hearing the prayers at synagogue services – though perhaps not quite in this way. Instead of the often forceful, booming presentation favoured by traditional cantors, Gesundheit’s ethereal voice (which longtime friend and collaborator Feist has noted is like “clear glass”) underscores the solemnity of the material. Accompanying her are sparse but striking melodies and instrumentation from collaborators such as Dan Goldman (Gesundheit’s musical partner in Snowblink), Basia Bulat, Sarah Pagé, Alex Lukashevsky and string arrangements by Owen Pallett, performed by the Macedonian Symphonic Orchestra.

“I think the thing I’m doing that I haven’t been able to find before is the ultra-traditional melody sung not in an operatic, grandiose way, but just in my simple, whisper-in-your-ear kind of voice,” Gesundheit explains.

“It’s important to me that it’s for a secular audience,” she says, noting that she listens widely to spiritual music that isn’t from her own tradition, such as gospel and Hindu devotional songs. “Of course, Jewish people resonate with it, which I’m so excited about, but it’s not for religious spaces – I wanted these experiences to be for everyone.”

Goldman, who co-produced the album with Gesundheit, recalls recording what were supposed to be some early demos for the project at his apartment in Montreal in 2017 the day after Gesundheit performed at a tribute concert to Leonard Cohen. He was already deeply familiar with the material, having overseen the sound mix at Shir Libeynu’s services over the past decade, and quickly recognized those early takes were special.

“We had just listened to Frank Ocean’s song Ivy one day – I started playing the song’s chords and Daniela started singing one of the liturgical songs over it. We looked at each other grinning with joy, and in an instant, we knew that the collision of worlds would totally make sense,” Goldman says.

Another collaborator, Toronto musician Johnny Spence, who played synths and piano on the album, remembers calling Gesundheit from Ireland on Yom Kippur two years ago – feeling melancholy at missing services back home, he was comforted by Gesundheit singing some prayers to him over the phone across the Atlantic.

“I’m Jewish and have chanted these prayers in synagogue all my life. These melodies hold my heart in an intimate and personal way, and having that relationship to the material certainly shaped how I approached this session compared to any other recording session,” Spence notes, adding that the project forced him to confront his own anxiety that “these songs aren’t meant to be recorded like this.”

For her part, Gesundheit recognizes she may face some backlash, particularly from more traditional members of the Jewish community who believe women are forbidden from singing in front of men.

“I’ve looked into that in Orthodox Judaism, and it all comes down to men not wanting to be aroused by women’s voices, or that it was distracting from their spiritual pursuits,” Gesundheit says. “So if I had been born 70 years earlier in my grandmother’s shtetl in Lithuania, none of who I am would have come to be – I couldn’t have done any of the things I’m meant to be here to do. I’m so grateful I was born into the situation I was, but how many women’s voices have we lost to that?”

Disrupting the traditional paradigm of having a group of men singing in the centre of the synagogue also affects the way the meaning of these songs of atonement is understood, Gesundheit explains.

“In the prayer Alphabet of Wrongdoing, you recite all the sins in alphabetical order – it’s one thing for a group of men to stand up and say together: ‘Oh, yeah, we’ve been bad,’ like a frat,” Gesundheit says, laughing, “but it’s quite another thing to have a woman stand up who’s maybe been the recipient of some of that wrongdoing – it’s just a different perspective. I hope it cracks people open in an emotional way.

“Most people, even really observant Jews who might disagree with my approach, if they’re paying attention they’d understand how important [this music] is to me,” she continues. “I’m not trying to disrupt for fun or frivolity. I’ve done some pretty deep investigations, and if I’ve made some changes, it’s because I think they’re meaningful changes.”

Gesundheit, who plans to release the full album early next year, recently posted the first two tracks, All Our Departed (El Malei Rachamim) and All Our Vows (Kol Nidre), online and hopes to perform the songs live for audiences who might be more familiar with Snowblink than the synagogue. In yet another take on tradition, she collaborated with Toronto designers Horses Atelier to create a performance outfit made of Jewish prayer shawls.

“I think the energy of the heart that she is able to conjure would come across in any language or musical tradition,” Goldman says. “The melodic turns may be unfamiliar to some, so for them, it may be a bit like travelling to a new country with all its novel scents, sounds, colours and textures.”

“I want to have this project express that our connection to whatever our heritage or tradition is doesn’t have to repeat verbatim the way our ancestors did for a really long time; that it’s sort of living poetry that we can write as we go,” Gesundheit says.

For Gesundheit, a dual Canadian-American citizen, the rise of anti-Semitism and other bigotry both in her homeland and elsewhere around the globe make her new project feel both timely and necessary.

“I keep consulting tradition because I also don’t want to go into the world reinventing the wheel every time. There’s so much beauty in our traditions, and I don’t see the point in just blanket-hating religion and discarding it,” she says. “There’s always something to salvage and to rework. But it does require having the space to do that, or giving yourself the space to have a different take on it.

“I want to collaborate with the equivalent of me in a Muslim community, or other people who have reworked their tradition and are looking for all the ways we can come together and not pull further apart – I really hope that’s what this [album] does.”